library(openintro)

library(tidyverse)

library(infer)

set.seed(1)Final paper

Introduction

Sports, particularly at high levels of competition, are often strictly gender-segregated. At the college and professional levels in the United States, men and women (people of other genders must generally abide by one of those categories to participate) generally play on different teams and in different leagues. Rules are often slightly different between men’s and women’s versions of a sport, and the set of sports available to women is slightly different than that available to men. This separation makes it possible for levels of resources to vary greatly between men and women. At the professional level, women’s leagues generally have lower viewership and attendance, less infrastructure, and lower athlete salaries than men’s leagues (Cooky, Council, Mears, and Messner 2021).

We would expect things to look different on the college level. Title IX, passed in 1972, was intended to prohibit such gender inequities in sports affiliated with most educational institutions. Was it effective? In this work, I address this by investigating the research question: How does the number of coaches assigned to US college sports teams vary by the gender of the team?

Data and methodology

To answer this research question, I use publicly available data on college athletics programs from the Office of Postsecondary Education in the U.S. Department of Education. This observational data is provided to the Department of Education by university athletic programs in order to comply with the Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act (EADA). It contains information on available sports, staffing levels, number of athletes, revenue, and spending, all broken down by team gender. This makes it an ideal data set for studying gender-based inequities in American university athletics programs.

The subset of this data that I will use contains information on the athletics programs at Duke University and the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill between 2003 and 2021. 879 unique teams are represented in this subset. In order to draw conclusions about differences in staffing between comparable men’s and women’s teams, I exclude all teams in sports that are only available for one gender, such as football and softball.

sports <- readRDS("sports_teams.rds")

sports_filtered <- sports |>

filter(

sport != "Baseball",

sport != "Field Hockey",

sport != "Football",

sport != "Gymnastics",

sport != "Rowing",

sport != "Softball",

sport != "Volleyball",

sport != "Wrestling"

)My response variable is the number of coaches assigned to a team. This includes coaches at all levels (assistant and head) and employee statuses (part time and full time). It is a discrete numeric variable ranging from 1 to 14 coaches, with a mean of 3.9 and a median of 3. It is right skewed: most teams have a small number of coaches and only a few have many coaches.

summary(sports_filtered$ncoaches) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

1.00 3.00 3.00 3.88 4.00 14.00 My explanatory variable is the gender of the team. This is a nominal categorical variable with two levels: “male” and “female.” There are 304 teams of each gender in this data set.

table(sports_filtered$teamgender)

men women

304 304 In order to examine the relationship between these two variables, I will use a one-tailed T test. A T test is the correct choice of hypothesis test for a question that employs a categorical variable with two levels as the explanatory variable and a numeric variable as the response variable. It will allow me to determine whether there is a statistically significant relationship between these two variables. I use a one-tailed test because my alternative hypothesis is directional—my alternative hypothesis is that women’s teams are less well-staffed than comparable men’s teams, while my null hypothesis is that staffing levels are the same regardless of team gender.

Results

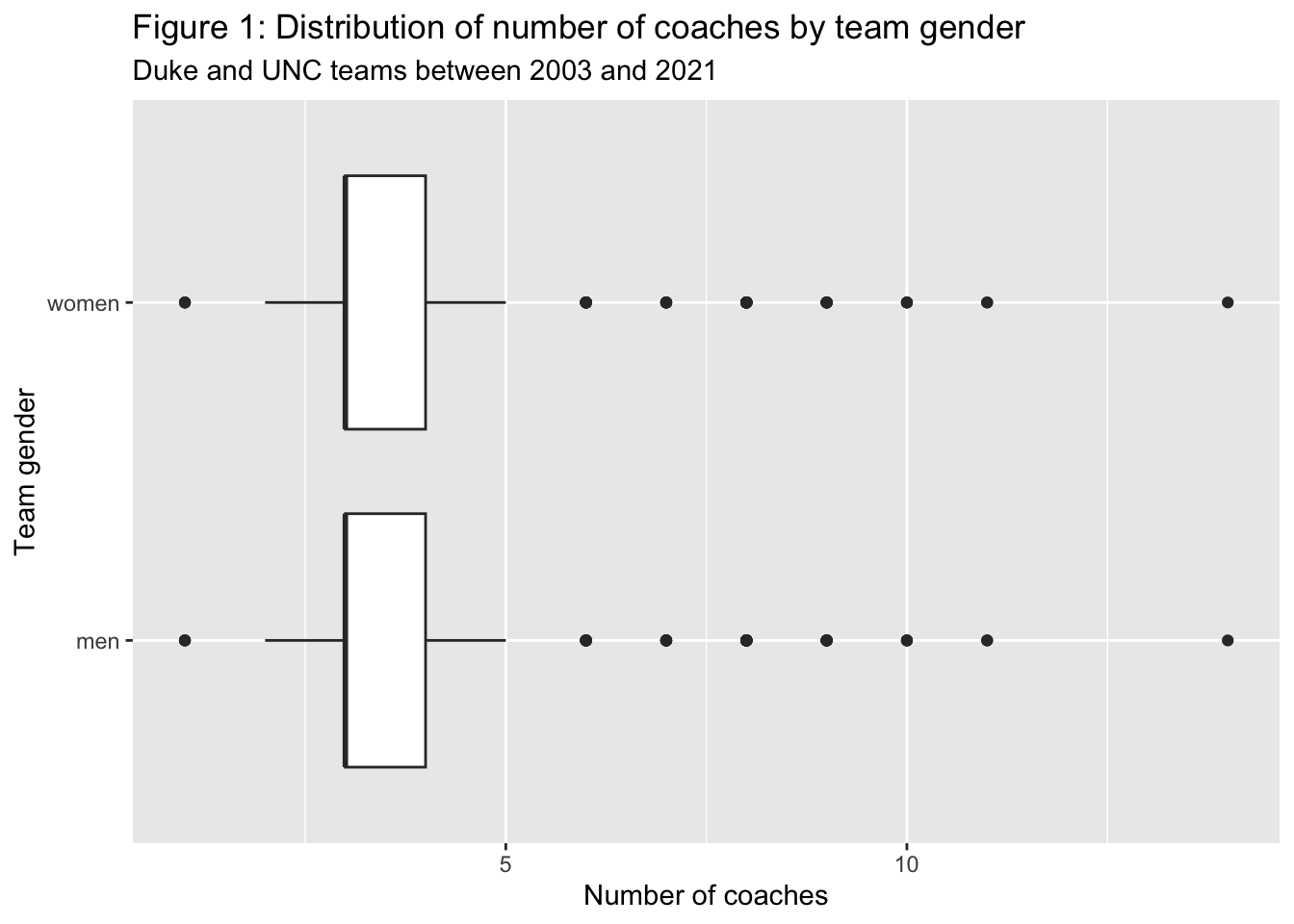

Figure 1 compares the distribution of number of coaches for men’s teams with that of women’s teams. If women’s teams are less well-staffed than men’s teams, we would see that the distribution for women’s teams would be positioned lower than that for men’s teams. However, there are no notable differences between genders detectable in this figure. The distributions for men and for women are both centered in the same place and have the same range and quartile divisions. If differences exist, they are very small and perhaps not very meaningful.

ggplot(data = sports_filtered, aes(x = ncoaches, y = teamgender)) +

geom_boxplot() +

labs(x = "Number of coaches",

y = "Team gender",

title = "Figure 1: Distribution of number of coaches by team gender",

subtitle = "Duke and UNC teams between 2003 and 2021",

fill = "Team gender")

Results of a one-tailed T test show that the relationship between team gender and number of coaches is statistically insignificant (p > 0.05). I fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between these two variables. In other words, these data do not provide evidence that there is any detectable difference between the number of coaches assigned to men’s teams and the number of coaches assigned to women’s teams.

sports_teststat <- sports_filtered |>

specify(formula = ncoaches ~ teamgender) |>

calculate(stat = "t",

order = c("men", "women"))

sports_nulldist <- sports_filtered |>

specify(formula = ncoaches ~ teamgender) |>

generate(reps = 1000) |>

calculate(stat = "t",

order = c("men", "women"))

get_p_value(sports_nulldist, obs_stat = sports_teststat, direction = "greater")# A tibble: 1 × 1

p_value

<dbl>

1 0.505Discussion and conclusion

In sum, using data on staffing levels in the Duke and UNC athletics programs between 2003 and 2021, I found that the number of coaches assigned to comparable men’s and women’s teams is very similar. This supports the theory that Title IX has been effective at negating gender inequities in resources in college-level sports. This work has several limitations that affect the scope of its conclusions, however.

First, only two schools are represented in this data set. Both are selective institutions with Division 1 athletics programs, and both are located in the same state. These results may not hold among Division 2 and 3 schools, which have smaller budgets and so may have different factors at play when choosing how to allocate funds. They may also not hold among schools in other parts of the country and other athletic conferences. Adding more schools, and a larger variety of schools, would strengthen the generalizability of these results.

Second, I did not differentiate between coaches at different levels, of different employee statuses, or with different levels of experience and skill. It is possible that the number of coaches assigned to comparable men’s and women’s teams is similar, but coaches for women’s teams are more likely to be part-time employees and so spend less time with athletes. It is also possible that there are differences in the salaries or benefits offered to coaches on men’s and women’s teams, which could result in coaches for women’s teams being less experienced or less skilled than coaches for men’s teams. Using different response variables that more thoroughly capture the characteristics of coaches would strengthen these conclusions by exploring some of these possibilities.

These results suggest several other fruitful directions for future work. First, coaching is only one of a host of resources provided to college athletics teams. Future work could investigate gender equity on other measures, like infrastructure and aid offered to athletes. Additionally, future work could more conclusively determine whether Title IX is what prevents gender inequity in sports, which this work cannot definitively speak to. Researchers could do this by comparing data from before and after the implementation of the law, and perhaps by using qualitative methods like interviews to explore the memories and motivations of administrators involved in decisions about resource allocation. Finally, future work could examine resource differences between the full set of men’s and women’s sports, rather than just those available to both genders. It could be that there are overall differences in coaching levels that are driven not by differential assignment of coaches to similar teams, but rather by the fact that different sports with different coaching requirements are made available to men and women. Now that we know that there are no detectable differences in comparable sports, investigating this alternate possibility is a logical next step.

References

Cooky, C., Council, L. D., Mears, M. A., & Messner, M. A. (2021). One and Done: The Long Eclipse of Women’s Televised Sports, 1989–2019. Communication & Sport, 9(3), 347–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795211003524