Good statistical practice: class wrapup!

Lecture 19

Duke University

SOCIOL 333 - Summer Term 1 2023

2023-06-21

Logistics

Presentations: Thursday June 22 and Monday June 26

Paper: Draft Monday June 26, final Wednesday June 28

Questions on instructions/requirements?

Today

- Wrapping up directions for future work

- Statistics best practices: where the field is at now!

Last time: Limitations and future directions

Directions for future work can come from limitations: how could you fix things for next time?

They can also be other kinds of extensions.

Future research builds on current research

Is there a new population to extend to?

Is there a logical next question to ask now that you know your results?

- Often that question is “why?”

Are there practical consequences of the results, and do those require further research to understand or mitigate?

Exercise Q1: Brainstorming directions for future research

- Write down an idea for a follow up study for each of these:

- Researchers surveyed 1000 British teenagers age 13-17 and found that higher rates of social media use are correlated with increased likelihood of anxiety and depression.

- In 1951, Asch showed that social pressure led undergraduate men to conform to incorrect suggestions.

- Using a longitudinal survey, researchers found that Americans who obtained a college degree between 1995 and 2000 got higher-paying jobs, on average, than people their age who did not obtain a college degree.

Revisiting p values

Exercise Q2: What’s a p value?

- A. A measurement of the size of the effect in a statistical analysis

- B. The probability of drawing a sample equal to or more extreme than the one you have, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

- C. The probability that the null hypothesis is true.

- D. The probability that the alternative hypothesis is true.

Exercise Q2: What’s a p value?

- A. A measurement of the size of the effect in a statistical analysis

- B. The probability of drawing a sample equal to or more extreme than the one you have, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

- C. The probability that the null hypothesis is true.

- D. The probability that the alternative hypothesis is true.

P values are the current standard for determining whether a result is important…

which is why we’ve spent time learning to calculate and interpret them

but they have some major problems! And things might (/should) change in future.

Problems with p values: cutoffs

Hypothesis tests (and other statistics): results are either statistically significant or insignificant

Cutoffs:

- Most common: p = 0.05 (1 in 20 chance)

- Sometimes: p = 0.1 (1 in 10), p = 0.01 (1 in 100), p = 0.001 (1 in 1000)

- Often multiple are reported: e.g., result is significant at the 0.05 level and 0.01 level but not at the 0.001 level

Problems with p values: cutoffs

Why those cutoffs? Why not something else?

- Absolutely no reason; they’re just nice round numbers (yikes…)

The “file drawer problem”

- Results with a p value of 0.04 are much more likely to be published than results with a p value of 0.06.

- But are those really that different?

- We lose a lot of information when we never hear about the studies at p = .06!

Dependence on sample size

We survey 200 people—100 living in North Carolina and 100 living in South Carolina—and ask them how happy they are on a scale of 1 to 10. We find that NC residents are .1 points happier than SC residents (NC mean 8.1, SC mean 8, standard deviation 2 points).

- p = .72—statistically insignificant; fail to reject the null

What if we instead survey 10000 people and find exactly the same thing?

- p = .012—statistically significant!

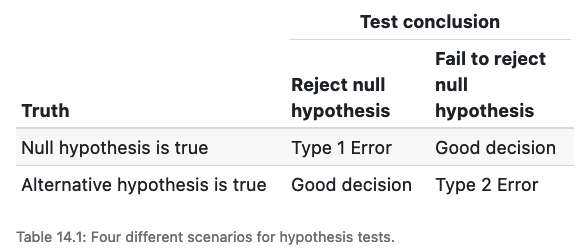

Errors

When there’s a cutoff, there’s the possibility of being wrong

- In either direction: you can reject a null hypothesis that’s true; you can fail to reject a null hypothesis that’s false

At p = 0.05, you will incorrectly reject the null (Type 1 error) 1 out of every 20 times–by design!

Effect sizes are essential

Effect size: how much of a difference is there?

P values tell you nothing about how big an effect is

They are determined more by sample size than effect size

Big samples: you’re more likely to find significant effects

- But those effects can be tiny and meaningless

Small samples: you’re less likely to find significant effects

- So you can miss “insignificant” effects that are actually real and important

Effect sizes

Effect sizes come from descriptive statistics!

What is the difference in mean/proportion/rate between groups?

- Ex: People who live in urban areas have an average of 0.3 more friends than people who live in rural areas.

For numeric explanatory variables: how much of a change in the response variable can we expect for a given amount of change in the explanatory variable?

- Ex: An increase of one hour of social media use per day is associated with a 5% greater chance of being diagnosed with depression.

Effect sizes

- What is “big enough” to be important?

- It’s SUPER dependent on context (don’t believe the internet when it tells you otherwise)

Effect sizes in relationship satisfaction

Study of 19000 people showed that people who met their spouses online were less likely to divorce (p < .002) and more likely to have high marital satisfaction (p < .001) than those who met their spouses offline.

But what about the effect sizes?

- Divorce rate: offline 7.67%; online 5.96%

- Happiness (1-7 scale): offline 5.48; online 5.64

It’s statistically significant, but is it important?

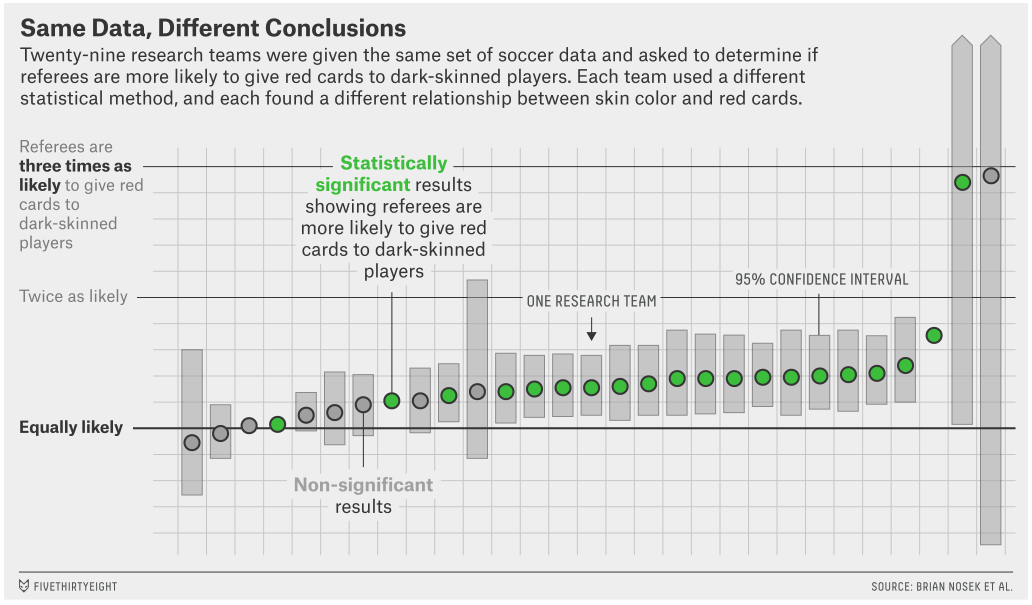

Different methods; different results

- P hacking: making different decisions about who to include/exclude or what your variables should be can change results dramatically

- Different statistical methods can also give different results

Different methods; different results

So what do we do??

- Descriptive statistics! Pay attention to how big your effects are. Statistical significance alone doesn’t make something important. Are the effects big enough to be meaningful?

- Be humble and be patient. One study doesn’t prove something. But evidence accumulates over time.

- Repeat things. If you find the same result in two datasets, or if you find the same result using different methods, it’s more likely to be real and meaningful.

Evidence accumulates

Objectivity in statistics

Objective analysis: 100% impartial, value-free, and unbiased

- Sometimes people think that if something is supported by statistics—ie, if the work is quantitative—it’s automatically objective (and qualitiative work is automatically not objective)

But statistics has always reflected the values, beliefs, and experiences of those who practice it—just like qualitative methods, but more sneakily

Wait a minute—how do my values have anything to do with how I run a hypothesis test??

Exercise Q3

- Values/beliefs/experiences come into it when analysts make decisions.

- Brainstorm: what are some decisions that people have to make in the course of an analysis?

A few examples of statistical decisions

- What questions to ask

- What data to use or collect (and from who)

- What variables to use and how to measure them

- What statistical methodology to use

- Which results to report

- How to interpret them

Statistics are not bad!

- No method is 100% objective. But they can still be tremendously useful.

- Statistics can be rigorous and fair while also being guided by analysts’ experiences and worldviews

- Analysts’ values/experiences can strengthen statistics rather than compromise it

Good statistical practice

- A lot has been written about how to do statistics better—in particular, feminist and antiracist scholarship

- Is what you’re reading using good practices?

- Is your own work using good practices?

Good practices: the highlights

Transparency!

- Analysts should talk about decisions, assumptions, and limitations

- If work sounds super sensational, makes sweeping conclusions, or doesn’t come with a list of caveats, there’s probably a lack of transparency. Good science is slow and gradual!

Good practices: the highlights

P values are fine, but think about effect sizes too!

- Analysis is most powerful when both are used together

- We <3 descriptive statistics!

- Be skeptical of work that claims a significant effect and tells you nothing about how big it is

Good practices: the highlights

- Be mindful of how people treat and talk about social categories

Categories like sex and race don’t “cause” social effects

- Sexism and racism that people in different categories experience differently cause social effects

Not all people in a category will experience the same thing

- Statistical results are always approximations–there’s a lot of variation in individual experiences!

- Did the analyst consider the possibility of intersectional effects?

- Don’t believe sweeping claims about entire groups: “All Asian-Americans…”; “People without college degrees need to do X…”

Whose experience is treated as the norm and why?

- Older work tends to treat White people and men as a baseline, and compare other groups’ experiences against theirs… but there are more principled approaches

The bottom line

- Statistics is a useful and powerful tool!

- But it’s not magic—it won’t automatically give good results.

- Analysts have a lot of choices to make: what questions are answered, how they’re answered, how the results are interpreted

- How those choices are made is important! And we’re figuring out all the time how to do it better.

We’re all done!

- Determine topic ✓

- Find data; learn what observations and variables are available ✓

- Write research question ✓

- Describe distributions of relevant variables ✓

- Prepare data frame for analysis ✓

- Describe relationships between variables ✓

- Perform statistical tests/write models ✓

- Communicate results ✓