Limitations and directions for future research

Lecture 18

Duke University

SOCIOL 333 - Summer Term 1 2023

2023-06-20

Logistics

Finishing up the project:

Results (component 3): Due 11:59pm tonight. Push to GitHub.

- I will get your grades back ASAP, prioritizing folks who present Thursday

Presentations and paper: instructions and paper example are up!

- Presentations: Thursday June 22 and Monday June 26

- Paper: Draft Monday June 26, final Wednesday June 28

Workshopping the project: your feedback

Why workshop? My theories:

- You start your work sooner—less crunch right before the deadline; you have an opportunity to ask questions if you get stuck

- Both giving and getting feedback are useful for learning this stuff

But maybe it doesn’t work–that’s okay too

Tell me (anonymously):

- Do you think workshopping the proposal and results was a good use of class time? Why or why not?

- What has been useful about this structure for you (submitting drafts for grading first, workshopping, then later submitting for grading)?

- What has not been useful/what would you change about it for next time?

- Any other comments for me?

Today

- Finishing up limitations and causality

- Directions for future research

- Problems with p values

Last time

Limitations: Your work can’t tell you everything!

- Sampling and generalizability: are the people in your sample similar enough to the people in your target population?

- Accuracy: is your data correct?

- Operationalization: did the people who collected the data measure what you would have wanted them to measure in the way you would have wanted it to be measured?

- Causality: do your results tell you something about why something happens? Or just about what is happening?

Association vs causation

- Association: two things are related

- Causation: one thing drives another thing

Requirements for determining causation

Covariance: There has to be a relationship between two variables

Plausibility and spuriousness: does it pass a gut check? do we know that there isn’t a third variable driving both things?

- Example: Ice cream sales are highly correlated with violent crime rates.

- https://tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations

- Experiments take care of this!

Time order: did the cause happen before the effect?

- Do we know that for sure, or is it ambiguous based on our data?

- Consider reverse causality

- Example: We survey 1000 people and find that people who have desk jobs are less healthy than people who have active jobs.

Exercise Q1

Are these statements causal or associative?

- Higher rates of social media use are correlated with increased likelihood of anxiety and depression among teenagers.

- Social pressure leads people to give answers they know are incorrect.

- People who graduate from college get higher-paying jobs, on average, than people who do not graduate.

Exercise Q1 solutions

Are these statements causal or associative?

Higher rates of social media use are correlated with increased likelihood of anxiety and depression among teenagers.

- Associative

Social pressure leads people to conform to ideas they know are incorrect.

- Causal

People who graduate from college get higher-paying jobs, on average, than people who do not graduate.

- Associative

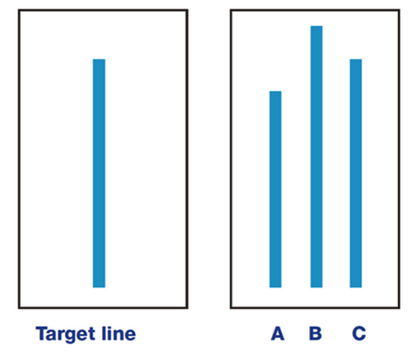

A brief tangent: The Asch Conformity Line Experiment

- Which of the lines on the right (A, B, or C) is most like the target line?

- What if six people before you all said B?

- Result: 75% of subjects (male-identifying undergraduate students at one university) gave at least one obviously wrong answer over the course of 12 trials. Less than 1% did in a control (no social pressure) condition.

Exercise Q2: Identifying limitations

- Write down a limitation for each of the following:

- Researchers surveyed 1000 British teenagers age 13-17 and found that higher rates of social media use are correlated with increased likelihood of anxiety and depression.

- In 1951, Asch showed that social pressure led undergraduate men to conform to incorrect suggestions.

- Using a longitudinal survey, researchers found that Americans who obtained a college degree between 1995 and 2000 got higher-paying jobs, on average, than people their age who did not obtain a college degree.

Turning limitations into next steps

- Limitations don’t have to be bad. Imperfect data is often still useful.

- Your limitations are often where ideas for future research come from.

- Can you think of ways to address the limitations in a future study?

Identifying other directions for future work

Future research builds on current research

Is there a new population to extend to?

Is there a logical next question to ask now that you know your results?

- Often that question is “why?”

Are there practical consequences of the results, and do those require further research to understand or mitigate?

Exercise Q3: Brainstorming directions for future research

- Write down an idea for a follow up study for each of these:

- Researchers surveyed 1000 British teenagers age 13-17 and found that higher rates of social media use are correlated with increased likelihood of anxiety and depression.

- In 1951, Asch showed that social pressure led undergraduate men to conform to incorrect suggestions.

- Using a longitudinal survey, researchers found that Americans who obtained a college degree between 1995 and 2000 got higher-paying jobs, on average, than people their age who did not obtain a college degree.

Revisiting p values

Exercise Q4: What’s a p value?

- A. A measurement of the effect size in a statistical analysis

- B. The probability of drawing a sample equal to or more extreme than the one you have, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

- C. The probability that the null hypothesis is true.

- D. The probability that the alternative hypothesis is true.

Exercise Q4: What’s a p value?

- A. A measurement of the effect size in a statistical analysis

- B. The probability of drawing a sample equal to or more extreme than the one you have, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

- C. The probability that the null hypothesis is true.

- D. The probability that the alternative hypothesis is true.

Cutoffs

Hypothesis tests (and other statistics): results are either statistically significant or insignificant

Cutoffs:

- Most common: p = 0.05 (1 in 20 chance)

- Sometimes: p = 0.1 (1 in 10), p = 0.01 (1 in 100), p = 0.001 (1 in 1000)

- Often multiple are reported: result is significant at the 0.05 level and 0.01 level but not at the 0.001 level

Cutoffs

Why those cutoffs? Why not something else?

- Absolutely no reason; they’re just nice round numbers (yikes…)

The “file drawer problem”

- Results with a p value of 0.04 are much more likely to be published than results with a p value of 0.06.

- But are those really that different?

Dependence on sample size

We survey 200 people—100 living in North Carolina and 100 living in South Carolina—and ask them how happy they are on a scale of 1 to 10. We find that NC residents are .1 points happier than SC residents (NC mean 8.1, SC mean 8, standard deviation 2 points).

- p = .72—statistically insignificant; fail to reject the null

What if we instead survey 10000 people and find exactly the same thing?

- p = .012—statistically significant!

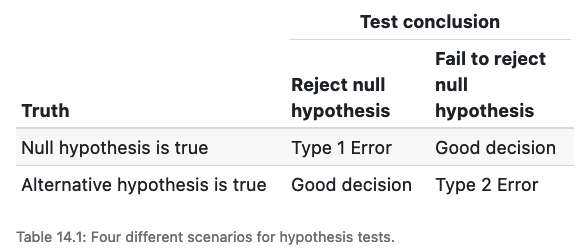

Errors

- When there’s a cutoff, there’s the possibility of being wrong

- At p = 0.05, you will incorrectly reject the null (Type 1 error) 1 out of every 20 times